unije

i don’t really know how to write about this. the fact is that, no matter what i say, or how i say it, there are some experiences that are intensely personal in a way that doesn’t translate into words. so i can’t explain why it meant so much to me to see the little island of unije, where my grandfather was born, any more than i can adequately explain why my surname matters so much to me.

it just does.

americans are, by definition, immigrants – it is as much a part of our identity as anything we call our own. ask any american where they’re from, and they can proudly tell you the different ethnic heritages they are descended from. we are american, yes – but we are irish-american, african-american, vietnamese-american.

me? i’m a second generation croatian-american, from croatian grandparents on my dad’s side. my grandfather’s immigration story is a typically american one, right down to becoming part of the great melting pot. it is so typical, in fact, that most of the families of unije, croatia also have a story like mine.

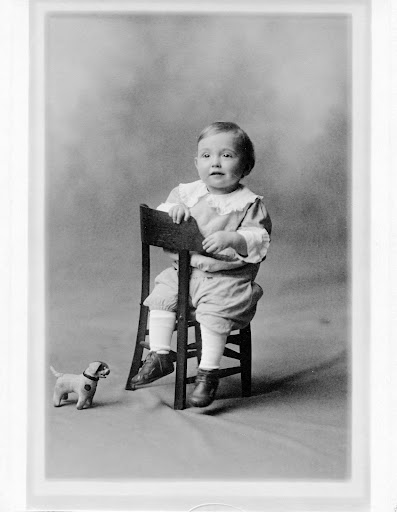

my grandfather died in 1993, and the memories i have of him are distinctive, sharp and clear – he is etched in my mind as a deeply tanned, square jawed sailor, standing astride his boat, backlit against a sea blue sky. but in many ways, poppi was always something of a mystery to me. he lived in florida, so i never saw very much of him growing up. when we did see him, he and my father often clashed in dramatic fashion – that scared me, and the force of poppi’s personality intimidated me. much of his personal ethnographic history has been omitted through the years – part of the common desire at that time to become a fully immersed “typical american” – so the family stories i know of him come to me secondhand, filtered down through his children.

and yet, the older i get, the more i see the reflections of him in my own father… and in myself. his effusive, emotional nature, the salt-water that ran in his veins, the stubborn streak at the core of him, the silver hair and prominent cheekbones. i have come to associate these as immutable family characteristics, passed down to me through genetics and upbringing. so for many years, now, i’ve wanted to see where poppi came from – the place and time that made him who he was as a young man setting out for the unknown shores of america. the land where he was born and raised, and the land he left behind. the land that launched this offshoot of my family tree with branches now so numerous and far-flung, it’s becoming hard to keep track. i wanted to see it for myself.

and it seems i’m not alone.

we first ran into silvana the evening we arrived, when we were sweatily, tiredly, grumpily chugging our way up the island’s highest hill, dragging our dusty wheeled case loudly behind us. she asked us if we were lost, and she wasn’t far wrong. we’d arrived at the island without any accommodation, somehow missed the island’s designated travel agent who met the ferry at the dock, and were now bumbling our way about trying to find a place to stay via the charitable assistance of the woman from the market – she’d made some calls on our behalf, then told us in broken english to look for a “blue house”. we were lost in a town of 200 people, looking for a blue house.

that blue house would turn out to belong to her niece (the travel agent we’d missed). when i mentioned in conversation with the niece the next morning that i had a family connection to unije, she passed that information along to her aunt, silvana. and so when i ran into silvana in the single-room town ‘market’, buying bread and cheese for breakfast, she stopped me and asked me about my surname.

silvana is a talkative, engaging woman in her mid-fifties, who happens to have been born on unije – she lived there until the age of 12, then immigrated to new york. after living in astoria, queens for most of her life, she recently moved back to unije a few years ago, and has become something of a local historian, actively working on island preservation projects, and keeping up the local lore. as a side hobby, she likes helping visitors to unije learn more about their ties to the island, and so it was that she approached me in the market, offering her assistance.

before i knew it, she’d asked around with some of the island elders and identified the house that my grandfather was born in (*), showed us some of the historic features of her own house, found someone who was probably related to me by marriage, and showed us where there were ancestors buried in the local cemetary. she told stories about island life before full electricity and telephones arrived in the late 70s/early 80s, when all communication was relayed through the post office and turning on a light switch in the middle of the day was a revelation. she spoke about how, to this day, whenever they receive notice that someone from unije has died, an old woman is dispatched to ring the church bell. she talked about how families used to farm their own food, and keep old stone barrels just for olive oil, and bake the day’s bread in a built-in bread hearth. she told us about the sardine factory that was closed, bought and re-opened by the state, then sold and closed again. she talked about the old families that left the island, the families that had returned, and the new residents from places like russia and bosnia who bought property and rented it out. she talked about the old women of the island who remember all the original families and their houses, and the arrival of the new rich yacht owners who anchor offshore in the pristine bays by the dozens. she discussed the change for the better (income from tourism, connections to the mainland) and change for the worse (the dying dialect, the increased litter and pollution).

she talked for hours, eager to share knowledge with those who came seeking on their personal quests. she told me about the newer phenomenon of people who are now several generations removed from the island, returning to explore their roots. these days, while visiting unije is logistically a bit of a pain, it’s far from insurmountable. complicating factors like political instability and civil war are now safely distant in the historical rear-view mirror. travel to and from croatia has become cheaper and easier than ever, and more and more individuals like me are taking the opportunity to see their ancestral homeland in person. every summer, she told me, she encounters people looking to trace their history – and it is those links which she believes will keep the essence of unije alive into the future.

her stories struck a deep chord, and as jonno and i spent the next day wandering the hill and coves of the island, taking photos, watching the sun pass along the sky and into the sea, listening to the background music of the waves and birds, eating grilled squid, drinking beer amongst the locals… i found myself trying to pinpoint more precisely what need this particular experience filled within me. as i ran my fingers over the stone walls of houses hundreds of years old, as i walked amongst the ruins of the old sardine factory, as i sought the shade of the olive trees, i couldn’t help but try to picture my grandfather’s life here as a young boy. and i felt the way i imagine adopted people searching for their birth history must feel: a longing for that sense of connection, that familiarity of seeing people who look like yourself, that internal, personal understanding of where you come from, not as an abstract idea, but as a tangible touchstone that slots into the foundation of *who you are*. and in seeking, finding a bit of who my grandfather was as well.

in a population of billions, this is a universal truth – we are all of us, searching for who we are in the world, and where we are from. for some of us, that is encompassed by a place, for some of us, a person, and for some of us, a purpose and future.

and in unije’s houses and families, crystalline waters, sunsets and fishermen, i somehow found a piece of all three.

(*) upon further clarification by a few other island elders, it turns out that was one of three houses that it might have been – oh well!